![]()

Eel

Joe Shute

At what point, I wonder, did she first sense danger? Was it the clang of metal crash barriers being locked into place and generator roar rippling down through the water, or perhaps the moment when the river itself started to move?

Even over the pull of the rushing weir, she would have felt the barrage of pumps being lowered upstream, each capable of sucking up 0.3 cubic metres of water per second; collectively able to swallow a river whole.

She would have detected the water level falling and city air encroaching from above – car exhausts intermingling with the familiar subaqueous scents of tyre grease, washing detergents, sewage overflow, rat piss and trout fluke. As the river receded, she must have also realised, with a jolt of panic, that her hiding places were drying up as the sunken treasures of Collyhurst Weir – an old bath and bicycle, a reef of car tyres, several knives and a box of bullets – emerged like shipwrecks at low tide.

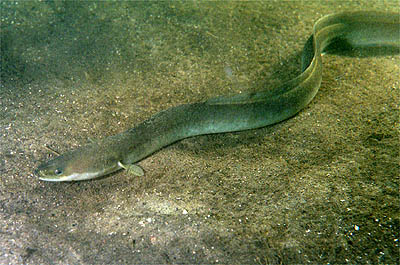

As torrent turned to trickle, she would have smelt the acid tip of the electric rod hooked up to a battery-pack lowered into the river and felt its charge course through the length of her body, nearly a metre long and streaked with silver, leaving her thrashing whip cracks in the shallows. As the stunned bodies of minnows, perch, three-spined stickleback and brown trout convulsed up to the surface, she twisted furiously away from the human hands reaching towards her, smashing herself against brick and ballast, writhing into silent S-shaped screams, every nerve-ending firing like after-burners to propel herself further downstream; until finally, she too was subdued.

It would have been quick. A matter of hours was, in the end, all the time it took for the entire course of the Irk to be halted, leaving behind a barren stretch of riverbed and exposing the mysterious creatures previously left to its depths.

She was discovered in the autumn of 2024, when the city authorities briefly changed the course of the Irk. As part of the Victoria North construction work, new service pipes containing electric and broadband cables were required to be extended to proposed buildings on the other side of the river beyond St Catherine’s Woods. The engineers involved decided that the best plan of action was to lay the cables in three conduit pipes concreted into a trench excavated underneath the Irk, but this required draining and diverting an entire section beneath Collyhurst Weir. ‘De-watering’ is the official term for such major work, like conducting open heart surgery on a river.

A dam and temporary pumping station were put in place above the weir, designed to block the river and re-route it through two outflow pipes which snaked along the riverbank before depositing the Irk 60 metres downstream. Video footage of this man-made Collyhurst waterfall shows the river’s entire force cascading out of the yawning one-metre metal gape of the pipes, furiously resuming its flow.

When the work was nearly completed, I visited the site to interview a few of those involved. They told me a team of ecologists had been recruited to collect any fish gathered when the weir was drained, but nobody had expected very much to be there. Instead, a treasure-trove of aquatic life was revealed: around 1,000 minnows, 20 three-spined sticklebacks, 100 perch and a large brown trout. Most exciting of all, however, was the discovery of five European eels.

The largest eel was a female, around one metre long, who had already metamorphised into a silver eel. This transformation is the final part of a roughly 20-year life cycle, where the female eel is gripped by a sudden urge to return to her spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea. To prepare for this epic journey, the eel undergoes profound physical changes; her eyes bulge, muscle mass increases and colour alters from a sickly yellow to metallic oceanic sheen. The eels typically wait until autumn before heading downstream and out into the ocean where they swim across the Atlantic to spawn and die. When the weir was drained, the fish were stunned using electric rods, collected into buckets, and then released 100 metres or so downstream; a small step on the eel’s 4,000-mile suicide mission home.

The weir had already been refilled by the time I visited, the pipes laid and river allowed to once more flow over its stone battlements first erected several centuries ago. As we stood and talked, I noticed a section of the riverside on the far bank where the brick wall had been damaged as part of the engineering work. Here the river was pouring into these gaps of fractured brick, fighting against its banks and pursuing a muscle memory of its former course. For Collyhurst Weir is a spot where the natural flow of the river has long been altered by human design.

This was the site of Travis Isle, a place where the Irk briefly divided creating an island around a quarter of a mile long. This island is apparent on William Green’s 1787 map of Manchester, where the Travis Mill sits on the smaller section of the river. The meandering route of this upper stretch suggests it may have been a naturally-formed split, but a weir was also built to encourage water running through the mill. Towards the end of the 19th century, this upper loop was removed and the river engineered into a single flow to accommodate the expansion of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. A notice published in the Leeds Mercury in 1877 describes the company’s intention to ‘divert the River Irk’ at Travis Isle. By the time of the 1891 Ordnance Survey map of Manchester, the upper section of river had vanished altogether. In this gap of riverbank wall, I realised, I was watching the Irk attempting to break free of centuries of confinement – a river retracing its former sinuous flow.

This is an extract from one of the creative chapters as part of Joe Shute’s upcoming doctoral thesis. It is entitled ‘Eel’ and is themed around the surprise discovery of a European Eel at Collyhurst Weir on the River Irk in 2024.